Nicole Estrada (she/her/hers), current NISGUA Internacionalista, wrote this letter during the COVID-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter uprisings in the U.S.

Picture of a dreamy trail in Birmingham, AL

Dear friends, family, and comrades,

It’s officially Leo season, and so much has changed since the last time I wrote y’all. I’ve been working remotely from Birmingham for 4 months now and in this time, I have felt a lot of things. Anger at how these moments of crisis always disproportionately affect those who are the most marginalized, grief for all the loss of love and life that were in many ways preventable, grateful to be able to spend my first summer back in the South in a while and learn how to love a place that previously felt harmful, inspired to see all of the amazing work and organizing happening at all levels across the world, and lucky to have work I find meaningful. Every day I make calls to people we accompany to check in with them and be able to better understand/respond to what people’s current situations are like. This work brings me so much resiliency and hope to know that even across borders and during a pandemic, we are still showing up for each other, checking in, and continuing in our solidarity.

I had a hard time initially starting this letter because there is so much happening in Guatemala and the U.S. that I didn’t know what to choose to focus on. But the thing is, it’s all interconnected–this moment is showing us with astounding clarity that state and historical violence and repression rooted in capitalism, white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy, etc. is the real pandemic. From the transitional justice movement in Guatemala for #NoMásImpunidad (no more impunity) that seeks to hold those who committed crimes against humanity and genocide accountable, to the calls to #FreeThemAll and #AbolishICE and #DefundThePolice and demand #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd and all of the other Black people who have been murdered and harmed by the police–these movements are interrelated.

Some of the folks that I accompany are people who work on the CREOMPAZ case in Guatemala. To give a bit of context, CREOMPAZ was a military center in Cobán, Alta Verapaz during Guatemala’s Internal Armed Conflict (IAC). During the IAC, it was known as Military Zone 21 and operated as a detention and clandestine execution center. It is now a United Nations peacekeeper training base. Between 2012 and 2015, the Forensic Anthropology Foundation of Guatemala (FAFG) carried out exhumations at CREOMPAZ and found 558 human remains, making it the largest case of forced disappearance in Latin America. Eight former military officers are now on trial in the CREOMPAZ case for crimes against humanity.

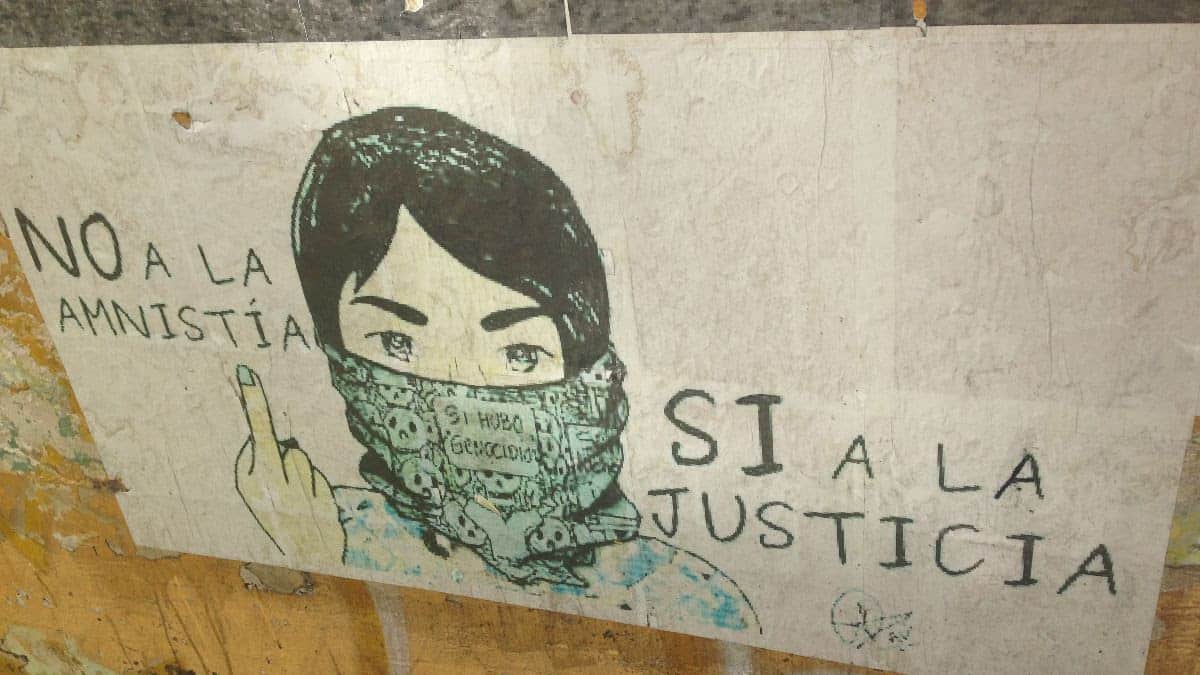

Photo of graffiti that reads, “No a la amnistía, si a la justicia. Si hubo genocidio,” which in English translates to, “No to amnesty, yes to justice. There was a genocide.”

Starting in May, five of the accused, currently held in preventative prison or military hospitals, were given hearings in which they requested to be moved to house-arrest, citing the COVID-19 pandemic as a risk to their health. The judicial branch has come to almost a complete standstill and claims to only be conducting essential hearings due to the pandemic, and yet, the courts prioritized these hearings for ex-militares accused of acts of genocide and continue to delay moving forward the processes of other transitional justice cases. The call from our partners and survivors of the IAC is clear: accountability and justice for the crimes against humanity and genocide that took place during the IAC–no more impunity. We see that the State continues to protect the interests of militares, big business, and the oligarchy at the expense of campesino and Indigenous communities through racism, corruption, and impunity.

This violence perpetuated by the State is also deeply linked to migration. During the IAC, many Indigenous people had to leave Guatemala because they could not safely stay in their communities. This trend continues today due to the government’s militarized protection of mega-projects that targets Indigenous land defenders and a lack of economic opportunities for people to be able to survive, among other reasons. In their migration processes, people are then criminalized and detained by hyper-militarized government agencies such as Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in the U.S.

Detention and incarceration is inhumane and ineffective ALWAYS and especially during a pandemic. People in cages are not able to effectively practice social distancing and are not given adequate supplies such as soap and masks to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. Transfers within the U.S. and deportations are propagating the spread of the virus. While in Birmingham, I have been involved with Shut Down Etowah, an abolitionist campaign made up of individuals and organizations seeking to close down the Etowah County Detention Center (ECDC) and County Jail in Gadsden, AL, which is notorious for its long history of human rights abuses and abysmal conditions. We have been involved in the nationwide #FreeThemAll campaign in response to the pandemic, demanding that those detained and incarcerated be released as a way of preventing a mass outbreak.

Picture of a Shut Down Etowah and Black Lives Matter Gadsden protest in Gadsden, AL on Father’s Day. Photo credit: Shut Down Etowah

A few weeks ago, Etowah confirmed its first cases of COVID-positive ICE detainees, and we know there is an outbreak under way on the jail side as well. In a petition to the public, people currently in detention make the connection between detention, police brutality, and state violence in their written statement:

“ ‘I CANNOT BREATHE!’ was what George Floyd cried out when the law enforcement officer kept his knee on his neck while George Floyd was helpless, defenseless and begged for his dear life.

‘I CANNOT BREATHE!’ we all ICE detainees cry out here at Etowah County Detention Center in Unit 9, as we too feel helpless, defenseless and beg for our dear lives. The law enforcement is keeping their knee on our neck by forcing us to live in an enclosed space occupied by more than 110 detainees.

Everyone in this unit is now sick for past week and as of today this whole unit is quarantined from people going in and out.

This civil detention has become a death sentence. ”

The State’s response to the Black Lives Matter protests make these connections even clearer. On May 31st, CBP announced that it was deploying officers to be used against protesters and sent a Predator drone over the city of Minneapolis. In Portland, we are seeing paramilitary-style tactics being used against protesters that “mirror decades of U.S. violence on the border and abroad,” including countries like Guatemala. This State-sanctioned violence has been occurring for decades against Black Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC), queer, migrant, and poor communities, and the uptick in these tactics that we are currently seeing is the government’s response to a mass movement that questions the status quo and threatens its power. Moments of crisis are also moments of movement-building, and we must keep up the momentum that we’ve seen grow over the past few months. It is also necessary, as we call to defund, to abolish, to tear down the systems that are killing us, that we imagine what liberation looks like, that we dream and start to build and create new ways of existing and relating to each other in this world.

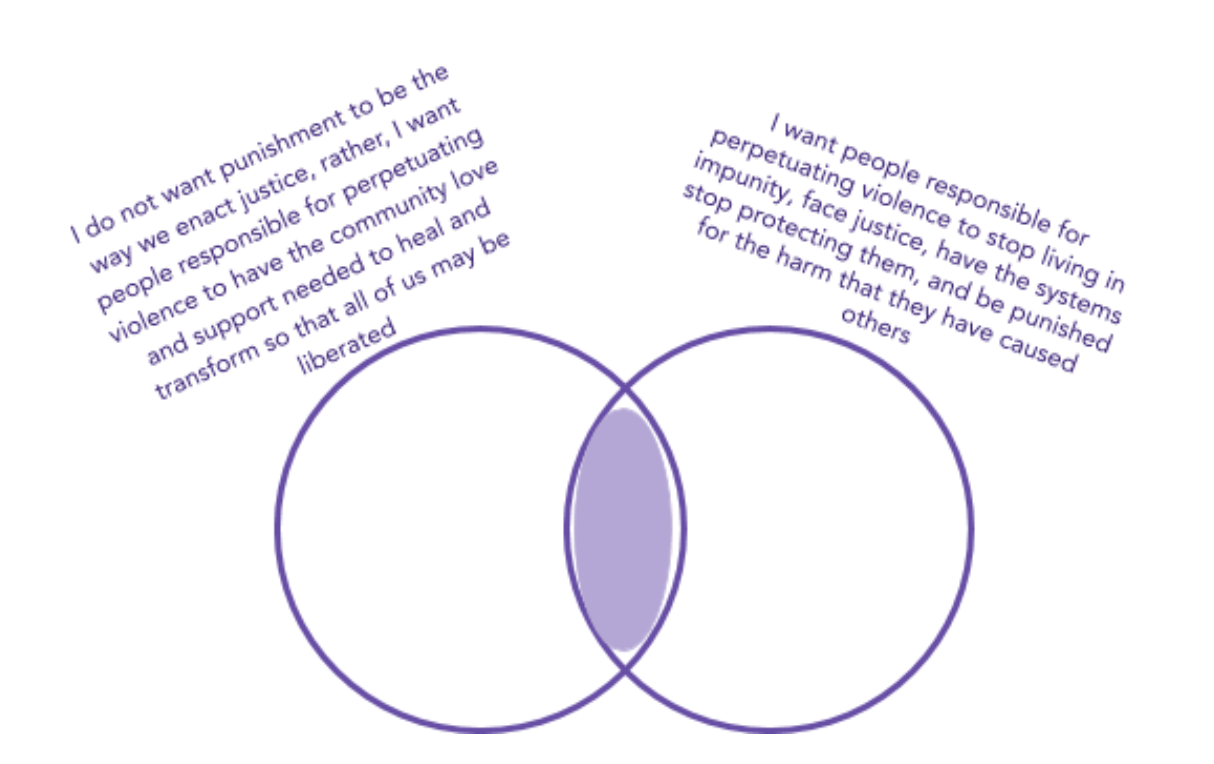

Being involved in the #FreeThemAll campaign while calling for #NoMásImpunidad and demanding #JusticeForGeorgeFloyd has made me have to think critically about what we are asking for. Because isn’t demanding that people be arrested, tried, and prosecuted for perpetrating State violence contradictory to the call for abolitionism? I’ve been grappling with this question for months, and all I can say is that it’s complex! We have built the world around fixed binaries, on the idea of right and wrong. This does not allow us to hold space to engage in conversations about the stuff that we’re not sure about, that isn’t easy to put a label on, that we’re afraid to talk about because then we have to admit that we’re still figuring a lot of this stuff out and that in that process, we make mistakes!

In Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, one chapter explores E.M./Elana Eisen-Markowitz and Rachel Schragis’ collaborative social media and art project, called Vent Diagrams, as a way to engage with complexity. They define a vent diagram as “a diagram of the overlap of two statements that appear to be true and appear to be contradictory. We purposefully don’t label the overlapping middle. . . . A good vent draws out a tension that we don’t have language for because that non-binary overlap isn’t really part of our public discourse (yet). By styling these tensions as unlabeled Venn diagrams, we get to a) actively confront binary thinking and b) imagine what’s actually in the overlap every time we see and feel the vent.” This is what my vent diagram has looked like in the past few months:

Image of a “vent diagram.” One side reads: “I do not want punishment to be the way we enact justice, rather, I want people responsible for perpetuating violence to have the community love and support needed to heal and transform so that all of us may be liberated.” The other side reads: “I want people responsible for perpetuating violence to stop living in impunity, face justice, have the systems stop protecting them, and be punished for the harm that they have caused others.”

For me, both of these statements feel true, and the process must be navigating the space where the two overlap. I believe in supporting the demands of survivors, which means that I want all of the ex-militares in the CREOMPAZ case and other transitional justice cases to be tried and convicted, to go to prison, for Guatemala to face the reality of the genocide that was committed during the IAC. I want people to be held accountable for the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and so many others.

At the same time, I want to envision a future where there are no more prisons, jails, or detention centers because we have seen time and time again that they only create more harm. I want to live in a world where justice is not rooted in punishment but rather, healing. A world that approaches this process through a transformative justice “approach to violence…[which] seeks safety and accountability without relying on alienation, punishment, or State or systemic violence, including incarceration or policing.” A world where, in the words of writer Kai Cheng Thom, we “collectively resist the culture of disposability that says that people who have done harm are no longer people, that they are ‘trash,’ that they must be ‘canceled.’ While consequences for harmful behavior are a necessary outcome of accountability, those consequences should not include actions that are themselves abusive.”

I’m still learning, growing, figuring out what I do and don’t believe in. That’s one of the most exciting things to me–knowing that there is still so much more out there to learn about, that I can continue to evolve towards compassion and love. Here I’m going to include some resources for self-education that I have found helpful, as well as some ways you can take action regarding the many things discussed in this letter. Thank y’all for reading and for showing me love and support in the various different stages of my life.

With love and gratitude,

Nico//Nicole

(she, her, hers)

Read:

- Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, edited by Ejeris Dixon and Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

- “A History of Institutional Violence at the U.S. Border” By Dévora González of School of the Americas Watch and Azadeh Shahshahani of Project South

Watch:

- “Portland Protests Grow Despite Violent Crackdown from Militarized Federal Agents & Local Police” by Democracy Now!

- “Paramilitary-Style Tactics in Portland Mirror Decades of U.S. Violence on the Border & Abroad” by Democracy Now!

Listen:

- “On Listening” by the How to Survive the End of the World podcast

Take Action:

- Join Shut Down Etowah’s call and email campaign expressing your concern about the current COVID-19 outbreak

- Support the Breathe Act, a modern-day civil-rights bill

- Stand in solidarity with Portland

- Tell your reps to end the immoral and illegal “safe third country” agreements

- Check out NISGUA’s solidarity in the context of COVID-19 for lots of action and mutual aid opportunities

- Donate to the Black Lives Matter Gadsden Bailout Fund to further the movement for Black lives in Gadsden/Etowah County

- Donate to Olla Comunitaria, a non-profit initiative started in Guatemala City that seeks to alleviate the problem of hunger with the current goal of delivering 100 lunches daily

- And, as always, donate to NISGUA 🙂

Leave A Comment