Michelle Liang (she/her) internacionalista 2023-2024 wrote this letter on February, 2024.

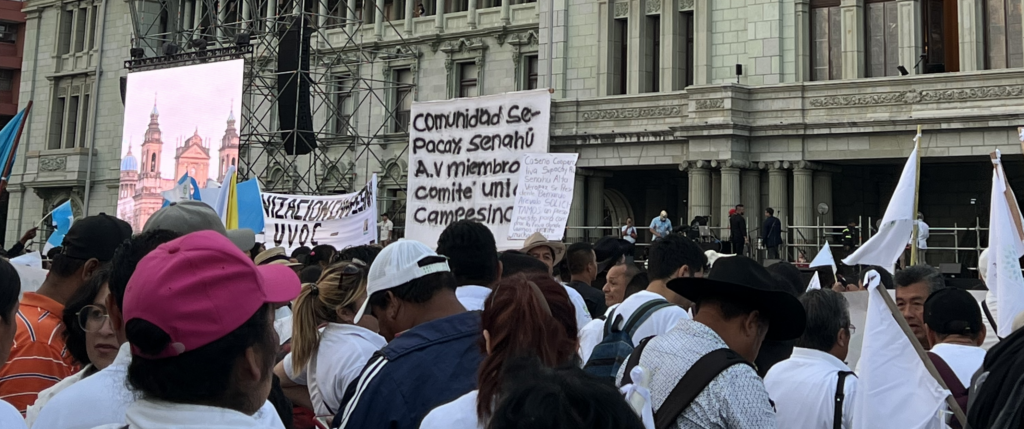

Photo by NISGUA Internacionalista. Guatemala City. January 2024

Thank you for reading! I had written this letter a while ago, but as it is time for my next letter… here it is.

A quick update first: After months of strikes, the people of Guatemala have WON. President Bernardo Arévalo was sworn in on January 14, 2024, although not without pushback. Up until the last minute, the opposition attempted to bribe Members of Congress for seats on leadership. Still, around midnight on January 14, I watched with many people at the Parque Central on the big screen as President Arévalo was sworn in.

This is only the first step towards justice, in the timeline of decades of resistance for land and water, and for recognition of and reparations for the U.S.-backed genocide of Indigenous peoples in the 1980s. After seeing Indigenous communities from hours away bus in to shut down the country, these struggles which are so grassroots, often volunteer-run by communities who have so little access to resources to begin with, by people living and fighting for justice in the campo (countryside), and sustaining 24 hour encampments against a mine despite how underresourced they are as movements and families, I cannot emphasize enough how Arévalo’s election is merely a seed- the power lies with the Indigenous people who see the election as potential groundwork for anti-corruption in this country, and justice in the world.

It is a strange position, to be a non-white accompanier. The role of an accompanier is to leverage our positionality, as someone from the Global North and privilege of nationality and citizenship status, to support, draw solidarity with, and amplify grassroots movements in the Global South, following the leadership and expressed asks of local leaders. Thus inherently in this role is privilege- the privilege to travel, the privilege of having enough financial stability to take the huge jump of leaving home and your family and quitting school/work/ whatever it is to do so, the privilege of a U.S. passport, the privilege of learning a secondary language for non-native speakers… (This last point I have been reflecting on- how it feels much more like a privilege to speak a secondary learned language as opposed to a native language. How when I speak Spanish in Latin America, I do much more unencumbered, whereas when I navigate Chinese in China, I always feel less than, judged, humiliated, laughed at for my imperfect Chinese- it has all the baggage of family trauma.)

Anyways.

I mean to say that inherently in the role of an accompanier is privilege. And, what allows me to take this dominantly white role is privilege. The disparities in class and access to resources could not be clearer when I meet with contrapartes.

So why do I flinch, why does my heart sink and my body disconnect from the conversation when a stranger or contraparte says, “La China,” or “Estás de los E.E. U.U.? Pero su cara es muy Asiatica”? Or, perhaps the most absurd: “You look like la chinita who drowned in the lake last month.” Almost without fail, at a 100% consistency rate, someone will pass a remark when they see me for the first time.

At first, it didn’t bother me; of course, since I stand out so much, people will wonder and have curiosity, as I would too; the truth is simply that there are not many Asian people in Guatemala. But after the comments that were less than innocent, after the repetition, all the comments began to blur together- and I would become triggered when someone passes even an innocuous comment.

It’s not that I want to be American, that I want to fiercely claim the identity of “I’m more American than anything else.” Why then do I feel this need to complicate their perception of me, to qualify that I was born in the U.S. and grew up in the U.S.? Do I also not clock when someone appears as though they are not from Guatemala; do I not have a spark of curiosity of who they are, what brought them here?

White accompaniers are expected to be here, traveling and colonizing and saving the world. Is it that I want to be that? The omnipresent white backpacker, anthropologist, voluntourist, global citizen? No, not at all.

Rather, it’s that the first thing I’m seen for is my race, which is defeating and dehumanizing – that no matter what presentation I try to put out, no matter how hard I try with my words or behavior, the first thing people will notice is my race.

It’s not that I don’t experience this in the United States, but perhaps in a different manner. Certainly, gender-based harassment is common as well, but somehow I am more used to that. And I would not doubt that the treatment of darker-skinned accompaniers would be wholly different and far more damaging.

I am here because of my privilege in nationality, citizenship status, ability to travel, finances, and more. And as certain East Asian Americans are acquiring more financial resources in the United States, stepping closer and closer to whiteness, my goal is not assimilation either. Nor I do not aim to compare marginalizations between myself and the communities here. Many times in my accompaniment role, I find myself unable to make sense of the global disparities of wealth, the injustice, and the power of isolation among the wealthy, abetted by the U.S. education system and the way capitalism sets itself up across large physical and mental distances (how easy it is to not know) – and even more so when I traveled for the holidays.

This is just a commentary on the role of an “international accompanier,” which is borne of differences in privilege, and what happens when non-white advocates from the United States begin to step into those roles- nothing more.

Donate to la Asamblea de los Pueblos de Huehuetenango en Defensa del Territorio por la Autonomía y la Libre Determinación de los Pueblos (ADH), a community of local land and water defenders, or to offset accompaniment costs (feel free to specify).

Leave A Comment