Oli (they/them), former NISGUA Internacionalista and forever compa, wrote this after their second stint as a volunteer in Guatemala with NISGUA.

During my first week back home in Philadelphia after accompanying in Guatemala, I finished the book Let The Record Show by Sarah Schulman about ACT UP and AIDS activism in New York in the 80s and 90s. Reading that book politicized me in new ways and I’m really grateful for the bridge that it made between Guate and here. I am making a zine about it, so this letter is kind of a first pass at those thoughts.

Let the Record Show is the first book I’ve ever read about AIDS history, although ever since moving to Philly I have picked up bits and pieces and threads of the history of the AIDS epidemic at art shows and in workshop spaces. (Before then I can’t remember ever learning much about it at all.) Learning about government neglect of HIV+ people in the US unexpectedly brought me to new understandings about state-led terror in Guatemala; not necessarily because the state actions resemble each other but because the popular movements fighting for life in both cases do.

Book cover of Sarah Schulman. Let the Record Show. A political history of Act Up New York 1987-1993

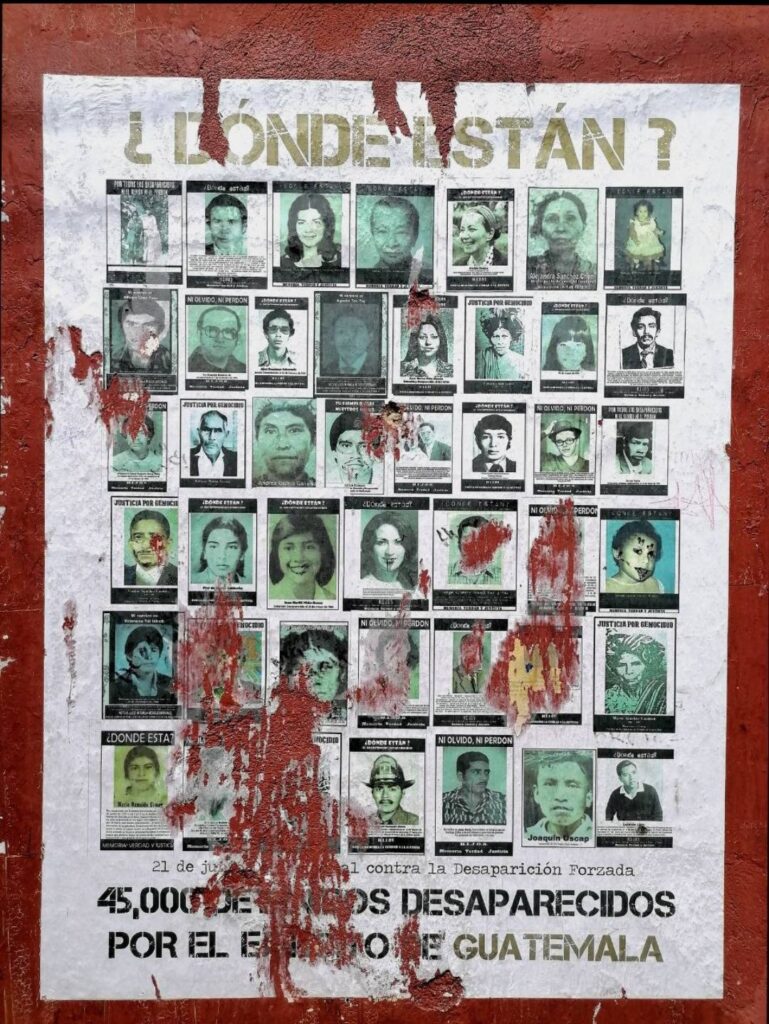

It has always had a great impact on me to be in spaces in Guatemala that are filled with people who survived the Internal Armed Conflict and had family members taken from them during it. The weight of absent beloved people is so large it’s overwhelming. It is nearly impossible to meet someone in Guatemala whose family was not impacted by the Internal Armed Conflict (which was instigated by a US-backed coup in 1956), and the city streets are papered with images of people who were tortured, disappeared and assassinated — students, labor leaders, campesines, parents, siblings. These images are pasted up by political collectives like HIJOS who refuse to forget them or forgive the state for their deaths, taking public space with their images and stories, often demanding to know, ¿DONDE ESTAN? / WHERE ARE THEY?

Photo by: HIJXS Guatemala. Junio 2021

In Let the Record Show, interviewees who were members of ACT UP remember countless dead friends and comrades. Sometimes it seems really important to them to simply mention names, sometimes they include one prominent memory or some detail they want to be remembered, sometimes they speak paragraphs. After listening to all 28 hours of the audiobook, I had heard hundreds of names and truncated versions of these stories — lives that ended very young, many of them using their last vital energies to try and convince or force the government, the FDA, and the CDC to take the AIDS epidemic seriously, fast-track drug trials, expand the definition of AIDS to include women (who for a long time didn’t qualify to participate in drug trials until ACT UP succeeded in changing the official definition), and, in short, treat them as humans.

It is grounding to remember that this really wasn’t that long ago, and the anti-trans attacks that we are living through now are part of a long continuum of violence. The relentlessness of ACT UP, and their brilliant diversity of tactics and visions, makes me ask myself how I can be less doubtful and less afraid to lose. As I learn about these people who should still be alive, I uncover a generation of queer compas that the world is so diminished without. I learn to miss something I didn’t even know I didn’t have.

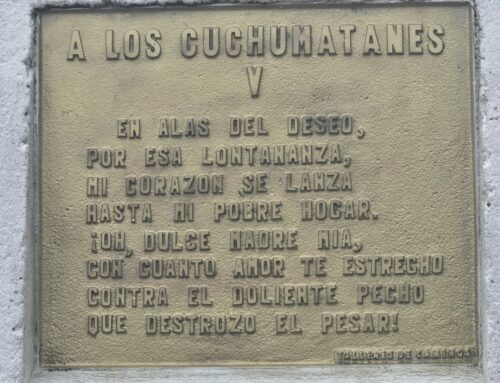

This experience has brought me to a new kind of empathy with those spaces in Guatemala that are filled with the ghosts and legacies of people whose lives the government took. It helps me to better understand the radical nature of the insistence on memory — I am living the consequences of never being taught queer history in school, and I learned about my ghosts almost by accident. In Guate, as here, many people understand that teaching real history is necessary for us to understand the world, and that insisting on remembering our dead kin – blood and otherwise – is both important for the orientation of the living and a material act of justice for the dead. MEMORY, TRUTH, JUSTICE is a common refrain in Guatemala – a graffiti tag, a call to action, a reminder that Guatemalans know what they deserve and will continue to fight for it.

![IMG_5471 [ESP] En una calle de guatemala, en el muro de un parque, hay un grafiti con letras blancas que dice: La memoria es justicia para nuestrxs abuelxs. [ENG] n a street in Guatemala, on the wall of a park, a graffitti with white letter said: The memory is justice for our ancesters](https://nisgua.org/wp-content/uploads/IMG_5471-1024x768.jpg)

Photo by Oli, NISGUA internacionalista 2023

I want to close by sharing two pieces of art. One is a spray painted message I walked by every time I went to the laundromat in Guatemala City – it’s on the wall of a park in zone 2. It says MEMORIA ES JUSTICIA PARA NUESTRXS ABUELXS – MEMORY IS JUSTICE FOR OUR ANCESTERS. This message caught my eye every time I hauled my dirty clothes and sheets to the laundry, and every time I carried the clean ones back home. Memory didn’t feel to me, at first, like anything material or satisfying. Memory was a tool used to win the real material things: court cases, exhumations and identification of remains, admissions of responsibility, laws, restitution.

But I was surrounded the whole time by lessons about how satisfying and powerful memory can be – there’s a reason, after all, that Guatemalan movement spaces are punctuated by anniversaries: days to remember massacres and assassinations, but also foundings of organizations, successful court decisions, community consultations. Remembering something every year is a way to make that knowing belong to the collective, to practice the importance of something many times over. Something changed for me with this graffiti tag that takes the power away from the court system or any other authority, and recognizes that it is already within the people, who by remembering their dead and their long struggle for justice, keep their fight alive and honor their grandparents. Memory is justice – as long as they are not forgotten, we haven’t lost.

![signal-2023-06-23-174523 [ESP] La espalda de una persona con una chaqueta de cuero y con letras blancas escrito: Si muero de SIDA, olvida enterrarme, solo arroja mi cuerpo en las gradas de la oficina de la administración de comida y drogas en Estados Unidos. [ENG] A persons back, with a black leather jacket with white letters: If i die of aids - forget burial-just drop my body on the steps of the F.D.A](https://nisgua.org/wp-content/uploads/signal-2023-06-23-174523-1024x1015.jpeg)

Photo by: Act-Up. https://www.artecompacto.com/podcast-arte-activista-con-andrea-galaxina/

And the second piece of art: there is a famous photograph of an ACT UPper wearing a leather jacket with their pink triangle (a subversion of the symbol used to mark gay people during the Holocaust) and the message IF I DIE OF AIDS, FORGET BURIAL – JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE FDA. The photo was taken by activist and lawyer William Dobbs at a 1988 action outside the FDA, and the person wearing the jacket is artist David Wojnarowicz. This image was something I had seen before really learning about AIDS, and it has a signature arresting tone that a lot of AIDS art-based actions had – an insistence that the FDA answer for its lethal inaction, but also a rejection of ordinary grief.

I’m grateful for the layers of remembering that led to me seeing this picture – the person making and wearing the jacket (wanting to be remembered), the person who photographed it, the many books and magazines and websites that have reprinted the photograph so that it is part of our public memory. The jacket echoes the public “political funerals” that ACT UPpers began to hold in the later years of the epidemic – a refusal to grieve quietly, an invitation to the public to join in mourning and demand action at the same time. The cardboard headstones and die-ins that ACT UP used early on turned into real funerals – in one mass action in October 1992, people dumped the ashes of loved ones who died of AIDS on the White House lawn.

![Screenshot 2023-06-23 at 5.53.40 PM [ESP] Una imagen en blanco y negro, de fondo una parte de la casa blanca de Estados Unidos en Washington D.C. Y sobre ella la silueta de una urna funeraria con letras adentro ilegibles. [ENG] A black and white imagen. At the background a part of the U.S white house in Washington D.C. Over this the shape of a funeral urn with ilegible letters inside.](https://nisgua.org/wp-content/uploads/Screenshot-2023-06-23-at-5.53.40-PM.png)

Let the Record Show is evidence that people did survive – Sarah Schulman and all the people she interviewed are doing the important work of memory by naming their dead friends. Hearing their memories helps me better understand who I am and what I want to do in the world. And one of the many lessons from Guatemalan organizers and family members of the disappeared is that memory creates power. They do not need to wait on any outside body – least of all the corruptest of all corrupt court systems – to verify their truth. They know, because they remember.

Leave A Comment