Oli (they/them) former NISGUA internacionalista wrote this update during their time as a volunteer with NISGUA. Read and enjoy!

Dear community,

I am in Guatemala for my second stint as an accompanier. Some of the struggles I accompanied when I was here last in 2018-19 have been won, or won for now, and it is a testament to the persistence of the land defenders here. I feel relief for this, and at the same time a lot of worry about how things have changed in the 4 intervening years — the levels of corruption and the total cooptation of the judicial system by elites and ex-military families can at times make it feel like justice is no longer possible in these conditions. But I know the people we accompany would disagree with me — one compa recently told us, in answer to a question about their future plans:

“We are not in a hurry. Our processes are generational — we know things might not change in our lifetime but we can’t expect the process to go in straight lines. Humans don’t move that way – we move in spirals.”

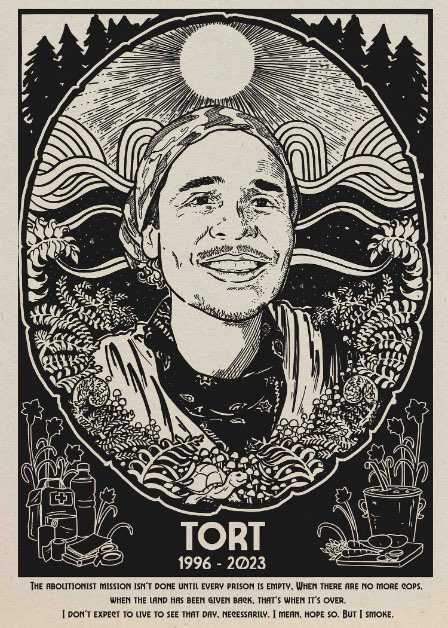

My heart has been heavy with news from the US, from the police murder of Tyre Nichols to anti-trans legislation that multiplies from state to state. The story of the Weelaunee forest defenders in Atlanta and the murder of Tortuguita (Manuel Esteban Paez Terán) has been especially present with me. It feels close to home. I want to dedicate the rest of this letter to Tortuguita and how their murder at the hands of police lends me a new understanding of land defense struggles all over the world.

Dekalb County, Georgia State police and SWAT teams leaving their command post in Atlanta on a tank. Source: Rolling Stone, 18 Jan 2023.

Being in the world of Guatemalan struggles gives me a different lens to see Tortuguita’s murder through. Here, like in other Latin American countries, environmental defenders have been killed by police, private security, and military alike, and in Guatemala where the memory of massacres during the Internal Armed Conflict is very much alive — where, for example, whole Indigenous communities were killed and removed from their land to make way for the Chixoy Dam — the deadliness of being a land defender is painfully clear.

There is a pattern that connects the threats against land defenders here to the militarization that the Stop Cop City protestors are confronting on Muscogee land in Georgia.

At its root, the confrontation is this: The view of land as a resource to be manipulated for profit, or exploited for some lethal end, is running headlong into people who have decided to align their bodies with the belief that there is immeasurable value in a forest continuing to be a forest. Of a river continuing to be a river. Environmental defenders are people who use their bodies to defend land and defend communities’ right to continue in uninterrupted relationship with land, partly based on the calculation that human bodies are granted a level of rights, respect, and sovereignty that our societies don’t grant to forests or rivers. They occupy a place like Weelaunee forest or the proposed site of the Dakota Access Pipeline, or in the case of some land defenders in Guate, simply exist on their land (meet with their neighbors, tend to their corn fields), on sites where some company wants to build a mine or dam. But increasingly in Latin America, and now ever more plainly in the US, respect for those people’s lives loses out in a battle with profit motives, with capital, with private investment or, in the case of Tortuguita, the alarming militarization of the police and the pursuit to control the majority-Black population of Atlanta with more practiced and resourced violence.

Why is life the negotiable thing here? Why, when these two forces clash with each other, is Tortuguita’s life the force that buckles and dies?

There are a lot of ways mainstream US culture doesn’t value life — most plainly in the constant police murders of Black people and ineptitude in the face of more and more mass shootings each year. Being so close to this context for my whole life can make it harder to see another way. In Guate I get glimpses of other ways – other ways to practice community safety, like in Indigenous communities in the highlands who hold community work days on Saturdays when all the families in a community help clear rocks from the roads to make them safe to drive on. I get glimpses of other ways to belong to a place — in the cosmovisions of Indigenous communities who relate to water as a living being who is the subject of rights. I know these examples abound within the US too, I just first encountered them here.

These other ways of viewing the world are so threatening to the interests of private investment, to the rich who have the Guatemalan state coopted, to the US economy that is designed only to grow, exploiting and consuming everything in its path – that their response is violent repression and criminalization. This has been the case with all the other alternative worlds that people have struggled to create inside the US for generations: Tulsa, Rosewood, the Black Panthers, the Red Power movement, etc.

Memorial poster for Tort. Source: JustSeeds

Criminalization, which is one strong parallel between the Weelaunee forest defenders and land defenders in Guatemala, is the targeting of leaders and movements through narrative and legal action; calling these leaders terrorists, dangerous, threats to society, and in some cases charging them with crimes that grossly misconstrue their actual actions. (The Weelaunee forest defenders are charged with terrorism for their occupation of a forest. Indigenous leaders in Guatemala have been charged with kidnapping for having meetings with their local mayors.)

Criminalization of land defenders is a tactic of alienation. It serves to make our bodies forget what our bodies need to survive. It serves to make our bodies forget what they know about other bodies: that they are fragile and sacred. That they need water. That they need oxygen, which trees produce. That they need forests, which are one of the biggest protections against the worst impacts of climate change. They definitely don’t need police with tanks and automatic weapons. They don’t need private investment projects that make rich people richer and displace Indigenous people from their ancestral lands. The narrative about land defenders has to be twisted so hard — they’re terrorists, they’re upsetting the public order, they’re not complying, they pose a threat — in order to push for the majority of us to align ourselves more with the abstract ideas of stability and economic growth than with actual human beings and the intuitive need we have for water, for air. They have to use fear to separate us from ourselves.

If we are to escape this trap, we have to feel our connections to the Weelaunee forest, to the Mississippi River, to Lake Superior, to the Amazon rainforest, to the Ohio River, to Lago Izabal and the Rio Cuilco — and to each other — more than we feel a connection to the goals of the police or of the the electric company’s private investors. In that sense, environmental defenders and others who defend life are very threatening: to profit, to capital, to growth. Because you have to endanger life to protect those things. And you have to threaten those things in order to protect life.

There is no other life for Tortuguita or for Topacio Reynoso or for Tyre Nichols. There aren’t ways to replace what a forest does once you tear it down. There are always other ways to keep us safe, to turn the lights on. It doesn’t have to be this.

A memorial to Topacio Reynoso, 16 year old anti-mining activist from Jalapa, Guatemala who was killed in 2014. Credit: Breaking the Silence

I am starting to know more viscerally what a lot of the world already knows: Life is the non negotiable thing. Profit can bend and break, projects can stall and fail, the police can dissolve and lay to rest their centuries of terror, but life is not the thing that breaks first. Life is sacred.

It hurts to live in a world that doesn’t know this. That keeps killing people by prioritizing money and “development.” For me, this is part of the why of building connections to Guatemalan struggles. Here, there are communities who know life is non negotiable, and they have ways of living and acting on that knowledge that I want to keep learning from for as long as I live.

They are calling Tortuguita’s murder the first murder of an environmental defender at the hands of police on US soil. This to me is an opportunity to see ourselves in the continuums of violence against the land in other places, and to see our rightful place in the continuum of land defense — we are already fighting the same fights.

Leave A Comment