In her final letter as a human rights accompanier in Guatemala, Clara Lincoln draws connections between the US and Guatemalan governments’ violence against indigenous peoples and people of color, through genocide, sexual violence, state brutality, and attempts at erasure through the imposition of mega-projects and gentrification models that strip people’s historic homelands.

The last witness for that day’s genocide retrial was called, Doña Magdalena de la Paz. Though the retrial of Efraín Rios Montt had ended with his April death, ACOGUATE continues to accompany members of the Association for Justice and Reconciliation (AJR), a national network of genocide survivors, as they continue to seek justice through the retrial of Mauricio Rodríguez Sánchez, Ríos Montt’s head of military intelligence. Wearing our bright green accompaniers’ vests, we accompany the groups of survivors through the various security checkpoints and in the courtroom, and back out. Increasingly, women in indigenous dress have been harassed by the security guards—asked to take off sweaters, asked what they’re hiding between their breasts, felt intimately under their belts at their waists. One of the days that I accompanied a group, one of the members of the AJR commented to us, “De todo nos querían desnudar.” (They wanted to undress us completely.) That statement sent shivers down my spine, a reminder of how sexual violence has been a tool to suppress indigenous women since 1492, prevalent in the internal armed conflict, such as in the sexual and domestic enslavement of the women of Sepur Zarco, and since.

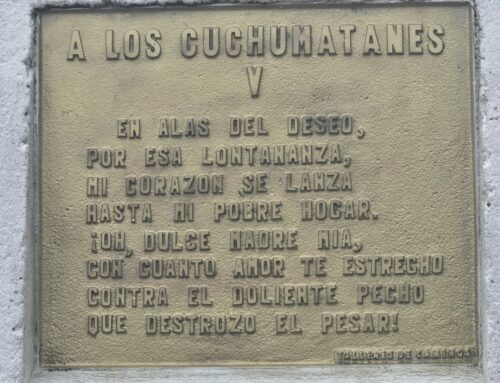

Photo Credit: José Rodríguez

In walks Doña Magdalena to face the judge: a short, plump indigenous Ixil woman in exuberantly colorful traditional dress. Her hair is braided into a crown with ribbons running through it, ending in pom poms that look like flowers. She is wearing an intricately-woven huipil and skirt. Over her shoulder she’s thrown a woven piece with a pattern similar to that of her blouse. She walks up a few steps and takes her seat between the two tables of lawyers as her Ixil-Spanish interpreter sits down next to her. In contrast to the last witness, a soft-spoken man who answered questions briefly and quietly, Doña Magdalena jumps at every opportunity to speak. The presiding judge has to go through a series of scripted questions before the lawyers get to ask questions. Doña Magdalena, however, didn’t follow the standard responses to the judge’s opening questions. How are people supposed to know that the standard response to “Do you know the accused?” is “No”? When the judge asked Doña Magdalena, she didn’t say no. She said she knew Rodríguez Sánchez. She said she knew he was responsible for the violence against her people.

Rodríguez Sánchez was head of military intelligence under head-of-state Ríos Montt from 1982-83. According to the International Justice Monitor, more than half the 200,000 murders and other violations that occurred during the 36-year civil war occurred in 1982. I’ll repeat: more than half of the violations in 36 years occurred in a one-year period under Ríos Montt and Rodríguez Sánchez. Doña Magdalena and the four other witnesses I have heard in the trials share stories of destruction and racism. They name their family members who died, either directly at the hands of the army or of starvation or disease hiding in the mountains. Doña Magdalena mentions that most of the babies who were born in the mountains died. Their cries risked revealing the people’s location to the army, so some mothers accidentally smothered their children to death trying to keep them quiet and safe. After every witness, the defense tries to twist their testimony to claim that the witnesses and their families were actually guerrilla fighters, meaning that the army’s violence was justifiable.

Ríos Montt and Rodríguez Sánchez. Photo Credit: LA Times

It’s hard to imagine, at least for me, why a government would enact genocide. The conflict in Guatemala can be traced back to US imperialism: the United Fruit Company, now known as Chiquita Brands International (the well-known banana producers), feared losing some of their immense stretches of land in Guatemala. Lucky for them, they had the director of the CIA on their board and had received legal representation from the Secretary of Defense; these two worked to induce a coup of the democratic-socialist president Jacobo Arbenz in 1954, setting in motion the repression that would turn into a civil war by 1960. But why the genocidal policies in the early 80s?

As an organization of mostly foreigners, we often ask Guatemalan activists to share their analyses with us. In January we invited a human rights defender and analyst to share her take on current events and the trajectory of politics and human rights in Guatemala. She shared her analysis that one of the goals of the genocidal policies in the internal armed conflict was to steal, kill, or run indigenous people off of the land in order to extract its natural resources. She shared that if you look at a map of where the most massacres happened and where the most megaprojects are today, the areas overlap noticeably. These are the same resources people are risking their lives and being incarcerated to protect today, one of the reasons I’ve heard people say the conflict never ended, it just changed shape. She called this strategy aburguesamiento of the land—gentrification.

I hear more and more connections between indigenous land struggles here and gentrification in the US. They are not always glaringly apparent, especially because here the struggles I follow are over rural land, and in the US gentrification usually refers the city. (There are also processes I would call gentrification in Guatemala City, but I haven’t had a chance to investigate these very much). The patterns are similar in rural Guatemala and urban US: poor people who have their roots and communities in a geographical space are run off—by military, by police brutality, by changing land deeds or by rising rent—and the economic elites get to act like it was theirs all along.

Another land-grab strategy in both the US and Guatemala is, ironically, declaring land protected or historical. Historical preservation in US cities is a way to protect buildings from being torn down, but it also has the effect of pushing out lower income people who happen to live in those areas. Anyone can apply for historic status for a particular building on the national, state or local level– and with that status comes tax credits and sometimes grants. On a WBUR Boston Radio segment, Meghna Chakrabarti says of historic landmarks, “We preserve these places for their architectural beauty, their historical significance, and the impact they had on society.”

However, according to many scholars, among those Sharon Zukin, Denise Lapenas, and Brett Williams, historic preservation can be a tool or unintended factor in gentrification of “historic” neighborhoods. Lapenas writes that this happens as the label draws more tourism, new businesses, and young professionals to an area, usually leading to increased property values and rent prices. As rent prices rise, lower-income residents are pushed out and forgotten about. Thus the strategy meant to protect locations with historical or architectural value has the effect of limiting who has access to those locations.

Declarations of preservation or protected land have been used as a pretext for displacement in Guatemala as well, a little more explicitly than in gentrification. In the department of Petén, a number of communities in an area called Laguna del Tigre have been violently displaced and criminalized. Petén is known for its major tourist attraction: the Mayan “ruins” of Tikal. Tourists flock to see the remnants of an ancient civilization, as if indigenous people didn’t still exist today, while 100 miles away in the same department of Guatemala, Mayan people are being kicked out of their homes– and even their country.

There are a number of communities in Petén, most of whom have been there since 60s and 70s. No one indigenous to Petén is still there, but the government has sponsored many programs to move peasants who don’t have land to Petén, and many displaced communities have landed there as well. This includes people displaced during the internal armed conflict. In 1990, the government declared the Laguna del Tigre and Sierra de Lacandón protected areas, imposing this designation on the people who already lived there. It is illegal to live in a protected area. Since then the communities have looked for a way to make their existence legal because, although many people were brought there through government programs, they have no legal recognition.

In September 2016, forty communities in these two protected areas proposed a development plan to Congress that would ensure their “perpetual permanence in harmony with nature in the territories that for us are fountains of life.” A few months after, the government emitted arrest warrants for many of the people involved. One of them, Jovel Tobar Rodríguez, was arrested in March 2017 for crimes of “usurpation of a protected area”. In June, his community, Laguna Larga, was violently evicted. One thousand Guatemalan police officers arrived to displace a community of 280 people. The police came and pushed them out, burning their houses and crops, much like displacements in the internal armed conflict in the early 80s. The inhabitants of Laguna Larga, like many of the displaced communities from these now protected areas, have had to take refuge in Mexico– just like their parents, or they themselves, had to do in the internal armed conflict. The Observer, an investigative journalism group that we work with in Guatemala City, wrote about the criminalization of Rodríguez, “Jovel’s arrest relates to the pretense of businessmen and the Guatemalan State of ‘sanitizing’ the territory in order to expand tourist projects, extractive developments, or to continue with impunity the illegal activities of the National Advisory of Protected Areas (CONAP).”

While these evictions have been happening, PERENCO, a French and British company, has been extracting petroleum and contaminating the area without legal consequence, and with many illegalities in their contract. Likewise, REPSA, an African palm company, was charged with ecocide for its poisoning of Río la Pasión, which resulted in people in surrounding communities contracting skin diseases and the destruction of the animal life in the river.

In Guatemala, just like in the US, land and its resources are the site of struggles for wealth and greed on one hand, and self-determination on the other. In both countries, declaring spaces historic or protected sometimes protects their resources—be they historical buildings, lumber, or gold—but often also displaces lower-income inhabitants. In the internal armed conflict, indigenous people were killed–one part racist genocide, one part land-grab. Those same land-grab strategies—displacement, violence, claims of ownership—continue today as the Guatemalan state and national and transnational companies scheme to take possession of land and its resources.

I didn’t realize how estranged my relationship is with the land I live on until I came to Guatemala and met people whose food, spirituality, work and home are all based in the land. People who are willing to fight, to go to jail, to die to protect their communities’ right to the land. I have newfound respect for people in the US who work the land and hold onto the connections that some of us have lost, but that our ancestors used to have—before industrialization, before globalization, and I would say, for some of us, before our ancestors sold out their roots in return for an identity of “whiteness.” Historical preservation is not the only way to preserve spaces and communities, but it could be a useful strategy for anti-gentrification movements. Anyway it’s a way to turn the typical uses of preservation on their heads and push ourselves to value people as much as places.

In Chiapas last year, in the context of one of the most dedicated and powerful collectives I have ever met, our trip coordinator from the Mexico Solidarity Network said that in the US, we have lost what community means. I believe that true change cannot come while we are disconnected from ourselves, from the people around us, and from the land – that’s one of the lessons I’m taking from working with land defenders in Guatemala.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

Leave A Comment