Since the mid-1990s, members of the NISGUA network have provided a physical international presence to threatened human rights defenders and communities in the Ixcán.

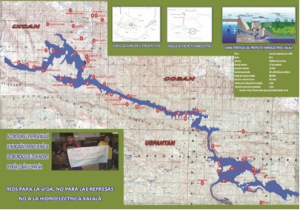

The river Chixoy, which runs from the south of Guatemala all the way up into Mexico, is the life that runs through both the geography of the region and the continued struggles that define our work there. The Cobán-Ixcán region is in the extreme north of Guatemala next to the Mexican border. Cobán is the municipality located on the East side of the river Chixoy. Uspantán. On the West side of the river and in the extreme Northern region is the Ixcán, which is where we will also be working. Surrounding these municipalities are many smaller communities connected often only by foot-trails through the jungle, pickups and small buses, or boats along the Chixoy.

|

| Burial of massacre victims in the Ixcán region, 1996. Photo credit: S. José Rio Negro, © A. Huet, Center for Independent Media |

Yet, hydroelectric projects do mean clean energy and development in a place isolated and beneath the shadow of extreme poverty. Several questions arise:

“Question:” Why don’t they want clean energy and development?

“Response:” If the Xalalá dam is built, over 50 communities around the Chixoy River will be either flooded or completely deprived access to water.

“Q:” What about relocation and compensation?

“R:” The Xalalá dam would be the second largest project in Guatemala next to the Chixoy hydroelectric project built in the 1980s. Those forcibly evicted from their homes and land at that time are still awaiting compensation.

“Q:” What about the trickle down affect of development projects, won’t they benefit in the long run?

“R:” The Xalalá project will create energy to be exported, not to be used locally. Those who benefit will be the elite who partner with international companies.

These questions are usually the first to arrive in the minds of people from the Global North, but the implications of damming this river go far deeper than questions of logistics and money.

The Indigenous Mayan peoples are the majority of the population in Guatemala with a culture and tradition alive as the river. The languages spoken in Cobán-Ixcán are principally Q’eqchi, Quiche’, Mam, and Spanish. The Mayan Cosmovision, or view of the world, emphasizes real connection to the Earth and the resources that are life for the Mayan peoples. The river is life, a life under threat.

|

| Indigenous Communities say NO to the Xalalá Hydroelectric project. Photo credit: NISGUA |

There has been no justice for the communities that survived massacres in this region during the armed conflict, instead there is continued tension and re-traumatization. This does not mean that they have given up, on the contrary, the tide for justice in Cobán-Ixcán flows strong. As an example, here is a time-line of their struggle against the Xalalá hydroelectric project:

- 2007 and 2010 – good-faith community consultations are held in Ixcán and Uspantán respectively. Over 18,000 community members, 90% of the population in the region, said NO to the project in these organized votes.

- 2008 – the community consultations, which are legal under International Laws of which Guatemala is a signatory, were ignored by the government and INDE started the project and began looking for investors.

- 2008-2013 – the Xalalá hydroelectric project is stalled by lack of investors due in part to the awareness raised by communities.

- November 2013 – a contract was signed by the Brazilian Company Intertechne Consultores SA to carry out the feasibility studies necessary for dam construction.

- April 2014 – the communities filed a injunction against contract in the Constitutional Court of Guatemala for illegality and irregularities.

- December 2014 – the National Electrification Institute (INDE) cancels the contract with Intertechne and declares that Xalalá is no longer a top national priority. The Constitutional Court has yet to give their decision on the legality of the contract and the people are suspicious of INDE’s change in tactics.

INDE has been using any tactic available to weaken the resistance of the local peoples to the project. They attempt to buy out local leaders, seize land in any way they can, start community strife to divide peoples, and offer much needed resources only in return for support of the project. They are even suspected of flying helicopters over these post-conflict communities to scare them into submission.

That is a part of the complex history of this region of Guatemala, so how does that translate to our work? As international human rights accompaniers in this region, my partner and I will provide moral support and a dissuasive presence to the communities and individuals who survived massacres as well as support individuals and organizations struggling against the Xalalá hydroelectric project.

Three of several of the organizations we partner with are:

1. AJR- the Association for Justice and Reconciliation- created by Guatemalan survivors and refugees to bring cases from the armed conflict to trial

2. ACODET – the Association of Communities for the Development of the Defense of Land and Natural Resources – communities in the area organized to resist the Xalalá hydroelectric project

3. Puentes de Paz- Bridges of Peace- they work in the region on several community support projects

They say that this region is the region of walking. From community to community we pack along our belongings and our notebooks, ready to listen to the voices of these powerful defenders and survivors, ready to share information globally to break the ugly silence and isolation in which oppression and violence thrive. I am so ready to learn from the undercurrent of strength that has sustained these people in their struggle, a struggle for the preservation of life, land, and water. In a world being drained of our human connection to nature, this is a struggle we all face together. The implications of their work and survival will be felt through Guatemala and through our global struggle for natural resources and human rights.

Thank you for reading this reflection, for taking time on your path to connect with me and with the people of Guatemala. Please check out www.nisgua.org for updates.

In Solidarity,

Kayla Myers

Leave A Comment