Nicole Estrada (she/her) wrote this blog while volunteering as an international accompanier in our GAP Internacionalista program. Her blog is here both as a text and an illustrated booklet — check it out!

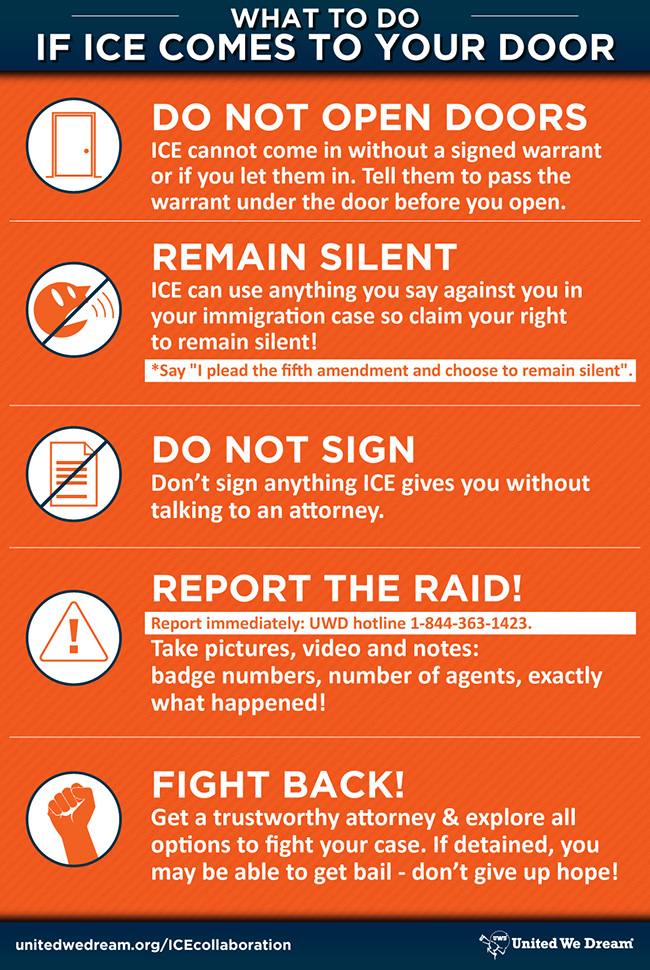

On August 7th, 2019, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) targeted seven different poultry processing factories across Mississippi. By the end of the raids, around 680 people were arrested, the vast majority of whom were undocumented Latinxs. Half of the total arrests came from a town called Morton, where these poultry factories (the largest of which is owned by Koch Foods Inc.) is the main source of employment. As a result, people were separated from their families, from their children, and were left without work. Many people are now forced to stay inside their homes for fear of being arrested and deported. ICE raids like these are designed to destroy the social fabric of migrant communities. The US uses this strategy to dissuade people from entering the US and, if they do arrive, to silence and invisibilize them as a way to keep them at the margins of society, where they can be more easily exploited. These raids are just part of a larger immigration and border policy that perpetuates violence against poor communities, communities of color, Indigenous communities, etc.

In this booklet, I will unpack the Trump administration’s immigration policies (not to say by any means that these problems didn’t exist before Trump), highlight what their impacts are, and show you how they affect and interconnect with the communities I have had the chance to work with in Guatemala. At the end, you will find a list of ~Action Steps~ that you can take after having processed this information. I hope that you find the time to read until the end, and remember: reading this is just the first step!

What is asylum?

According to US Citizenship and Immigration Services, “asylum status is a form of protection available to people who: meet the definition of refugee, are already in the United States, [and] are seeking admission at a port of entry.”

What is the criteria to be considered a refugee?

The 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees states that a “refugee” is “any person who is outside [their] country of nationality. . .and is unable or unwilling to return to that country because of persecution or well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.”

Things you should know about the asylum process.

The “Remain in Mexico” Policy, also known as Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), began in January of 2019. People seeking asylum in the US are being returned to Mexico as they wait for their cases to be processed in US immigration courts. This policy makes it hard for asylum seekers to access the legal support they need. In addition, most of these asylum seekers do not have legal immigration status in Mexico, which affects people’s ability to get jobs or have any sort of permanent life while they wait for their asylum claim to be heard.

After immense political pressure and threats of economic sanctions, the Guatemalan government signed the “Safe Third Country” Agreement with the US in July of 2019. This policy states that if migrants came through Guatemala on their journey and did not seek asylum there, then they cannot ask for asylum in the US. Similar agreements have also been signed in Honduras and El Salvador.

- Why not request asylum in another country before arriving to the US?

As of August 2019, Guatemala’s asylum agency has fewer than 10 employees and won’t be able to handle the influx of any sizable number of migrants (to give you an idea, in 2018, the US received around 2.2 million new migrants). Requesting asylum in another country such as Guatemala first would add even more time to the already current years that people are waiting to be processed for asylum. In addition, many critics have highlighted the fact that many migrants are coming from the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) itself, and that if this is not a safe enough territory for these Central Americans, it is not going to be safe to other migrants either.

As of July 2019, there were almost 900,000 asylum cases waiting for immigration hearings, which means that the current wait time for an individual asylum case to be decided is around 3 years. Even after such a long wait, asylum is very difficult to obtain. In the fiscal year of 2018, only 22,491 people were granted asylum in the US.

- “Metering” is the term that the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) uses for a process by which it limits the number of people who can request asylum at a port of entry at a US-Mexico border crossing each day. For example, at the San Ysidro port of entry, there are reports that US government officials will only accept 20 asylum applications per day.

What are the numbers? In August of 2019, a New York Times article reported that there were nearly 58,000 asylum seekers waiting on the Mexican side of the border for their chance to request asylum in the US. This is a compounded result of the “Remain in Mexico” and “metering” policies. Shelters and legal services organizations in cities on both sides of the border have struggled to keep up with the arrival of migrants. Some migrant shelters have begun to turn away new people due to overcrowding. Those who cannot afford to stay in apartments or hotels are forced to sleep in the streets as a result. In addition, migrants in Mexico face the threat of targeted kidnappings and violence.

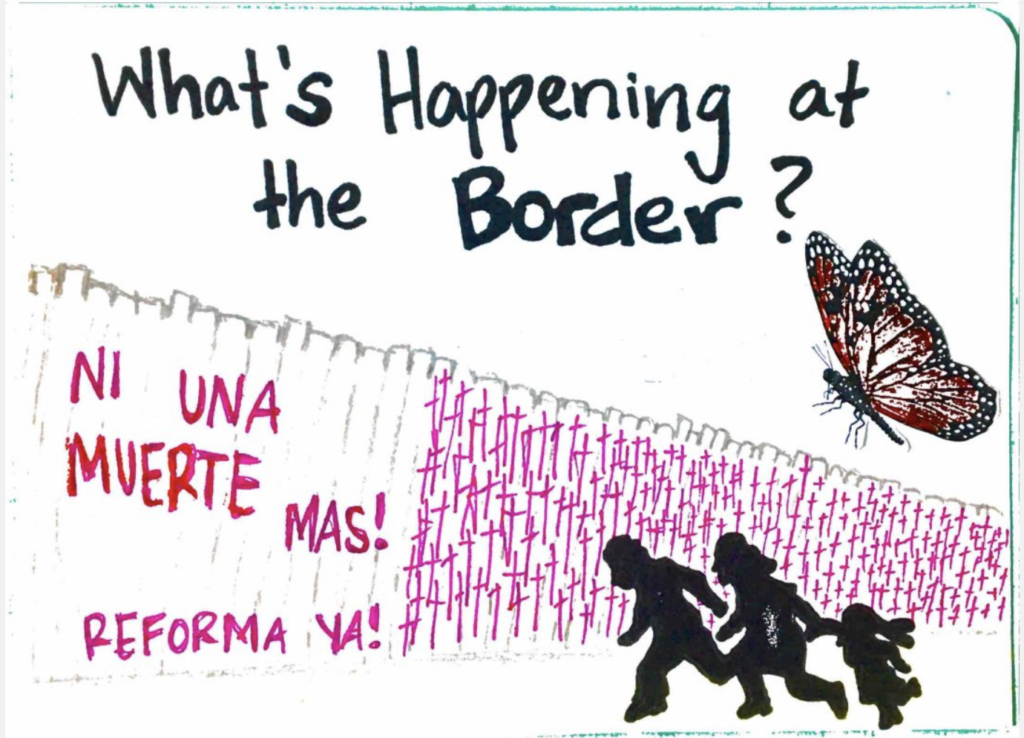

Death on the border. Many people are deciding to forgo the unending wait lists and risk an unauthorized border crossing, which brings with it a whole host of other risks such as kidnapping, extortion, rape and other sexual violence, disappearances, human trafficking, gang violence, deportation, and death. According to Migration Data Portal, between January of 2014-October of 2019, 2,243 deaths have been recorded at the US-Mexico Border. However, this number “represent[s] only a minimum estimate because the majority of migrant deaths. . .go unrecorded.”

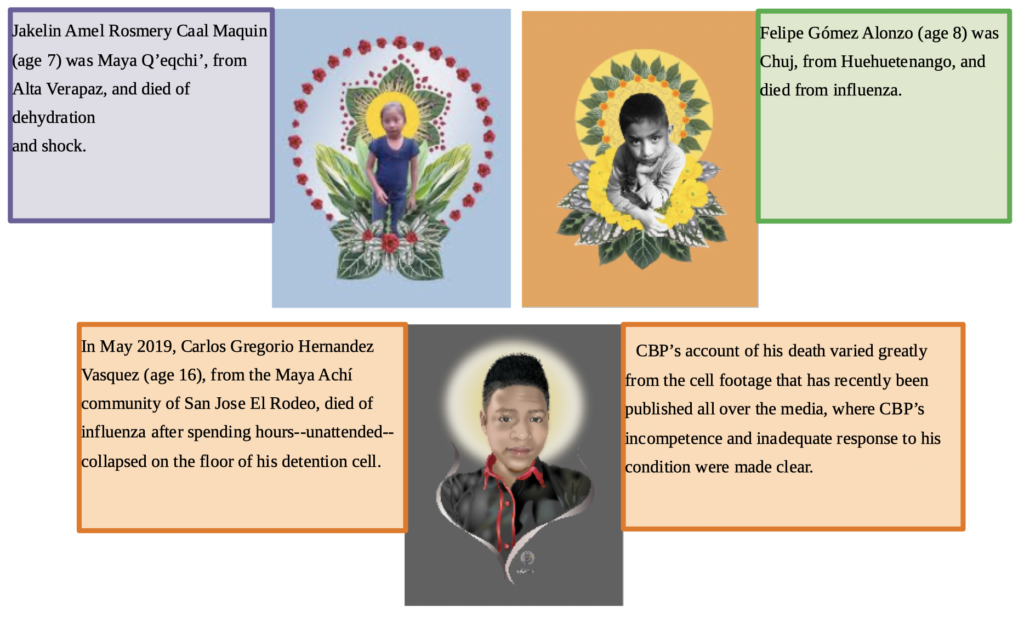

In the same month of December of 2018, two Guatemalan children died while in the custody of CBP.

Top artist credits: @broobs.psd. Bottom artist credit: lacorua.com

Asylum is interconnected with state and historical violence.

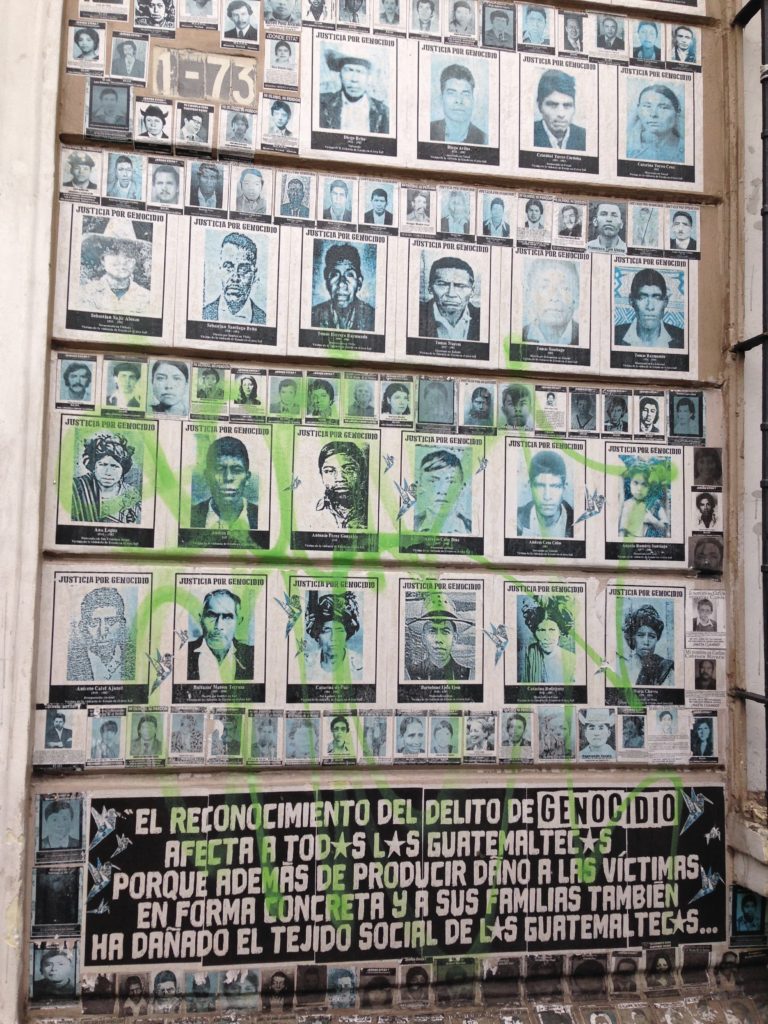

During my time in Guatemala, I came to hear about an organization called the Asociación para el Desarrollo Integral de las Víctimas de la Violencia en las Verapaces, Maya Achí (ADIVIMA; Association for the Comprehensive Development of the Victims of Violence in the Verapaces, Maya Achí). ADIVIMA is a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) that focuses on transitional justice work in the Maya Achí communities through the recuperation of historical memory and access to justice in the aftermath of the Internal Armed Conflict (1960-1996) and genocide that took place in Guatemala.

In May of 2013, the president of ADIVIMA was given the opportunity to speak at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, where he criticized the role that the World Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank had in financing the Chixoy Hydroelectric Project in Guatemala. The construction of this hydroelectric dam began in the 1980s. When people began protesting its implementation, their resistence led to the Río Negro massacres. This series of 5 massacres took place between 1980 and 1982 and took more than 5,000 lives, directly targeting the Maya Achí communities of Alta Verapaz. The Guatemalan state employed this strategy all across the country during the Internal Armed Conflict: committing genocide and displacing Indigenous communities from their ancestral lands to claim space for megaprojects to be implemented.

Guatemala City is covered by the faces of martyrs killed by the state during the Internal Armed Conflict.

Before the Forum, the president of ADIVIMA had already undergone arrest, defamation, and threats to him and his family’s lives due to his work as a human and environmental rights defender. Unfortunately, this is a similar narrative amongst activists in Guatemala—in 2018, over 30 human rights defenders were assassinated and Guatemala was the country with the highest rate per capita of land defenders murdered. After his participation in the Forum, the situation worsened when he found explosives hidden in his car. In November of 2014, he and his family were forced to leave Guatemala for their safety and arrived in the US, where they started the process to claim asylum. It took them more than three years before they were able to claim asylum. Fortunately, they had a network in the US that was able to support them during the waiting process—this is not the case for the majority of migrants hoping to make an asylum claim.

A vicious system. Many people criticize the border, the asylum process, and immigration law as being part of a “broken system,” when in reality, everything is functioning the way that the State and those in power intend. The system is not broken, it is a fine-tuned machine created to perpetuate violence against People of Color, Indigenous people, poor people, and to send them a very clear message: they are not wanted. It is not a matter of “fixing” this system—it is a matter of abolishing it.

More resources for further reading:

“No safe third country agreements with Central America” NISGUA report

No Wall They Can Build: A Guide to Borders & Migration Across North America

The Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj Volume 5: “Trump’s Worst Policy: Killing Asylum”

Leave A Comment