Claire (they/them), former NISGUA Internacionalista, wrote this update during their time as a volunteer with NISGUA.

Dear NISGUA family,

Almost exactly one year after leaving staff, I’m honored to come back for a month as an accompanier. Frankly, it’s a disturbing political scene to return to. You may have heard people say that Guatemala feels like it’s returning to the 1980s — it’s true, and it’s present on every corner and in every conversation.

It’s easy to lose hope right when we most need to get rigorous about building a positive future. Perhaps the greatest lesson our Guatemalan partners continue to teach us is the need for collectivity in our struggles; none of us know everything but together we know quite a lot. So today I want to invite you to join us in grappling with some hard questions that I’ll share below — can you talk about them with at least one other person tonight? Would you email us with your reflections? We need and want to hear from you.

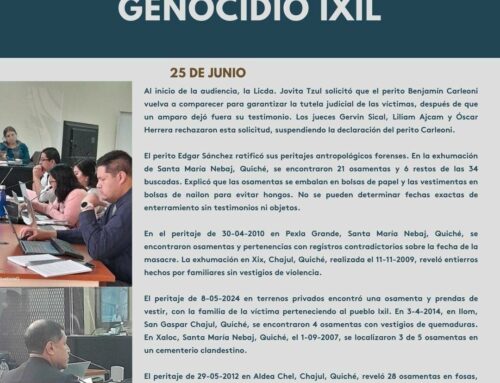

When I first came to be an accompanier six years ago, genocide survivors were certainly being denied the justice they deserve, but there was a sense of real possibility for transitional justice cases. Efraín Ríos Montt was the first former head of state *in the world* to be found guilty of genocide in 2013, previously “untouchable” military leaders were found guilty in the Molina Theissen disappearance case, and it looked like the historic Military Diary case was going to move forward.

These days, the vast majority of judges and prosecutors who made these historic advances possible have had to flee Guatemala or are facing criminalization and threats here. Zury Ríos, daughter of Ríos Montt, is forecasted to win the first round of presidential elections in June. Most experts identify the attacks on anti-corruption judges and prosecutors as a crucial part of Ríos’ long-term strategy to take power. After all, her inscription as a candidate is clearly outlawed in the Constitution, which does not allow the children of people convicted of genocide to run for president.

We ask ourselves: what does solidarity with survivors mean when the judicial system is coopted by the very perpetrators of genocide?

The 10th anniversary of Rios Montt’s genocide conviction is May 10th. Join NISGUA, in solidarity with survivors, by taking part in a decentralized action before or on May 10th. Tag us on social media or email pictures of your actions to organizer@nisgua.org with the hashtags #SíHuboGenocidio and #EnGuatemalaSíHuboGenocidio.

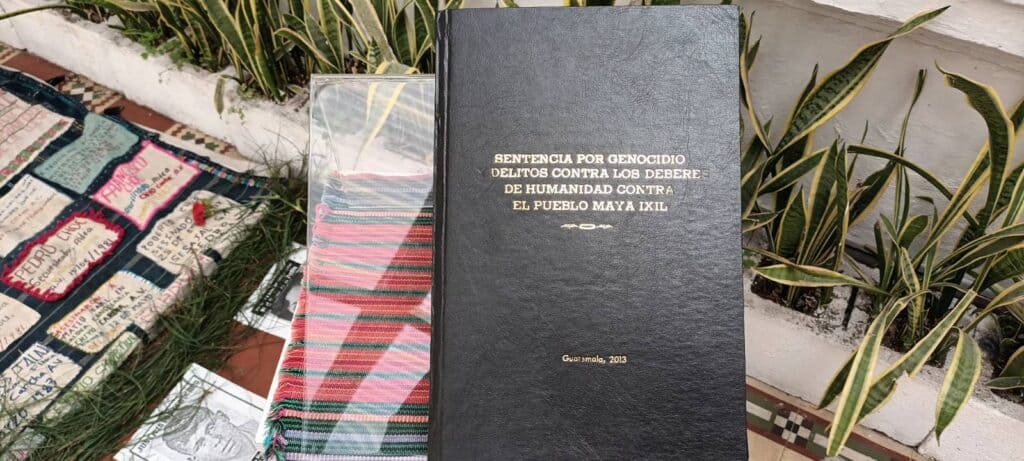

Photo of the Sentence for Genocide, Crimes against the Maya Ixil People. February 2023

A common right-wing lie in Guatemala is that frontline organizers are paid pawns of international governments and nonprofits. This argument is based on the racist idea that Indigenous and campesino/a/e people are not capable of envisioning and leading their own movements for self determination. That’s laughable — we all know that it couldn’t be further from the truth.

However, the “corrupt pact,” (an alliance between corrupt politicians and their financiers in the oligarchy) has successfully weaponized this lie into the NGO Law, which has put an impossible regulatory burden on nonprofits and forced many international organizations to stop their financial support of human rights defenders. What’s more, worldwide we’re seeing the international cooperation slash its budgets for human rights work in Guatemala, leaving some organizations with almost no budget practically overnight. People have long criticized the “NGO-ization” of social movements worldwide as unsustainable and unprincipled.

What can people-to-people solidarity offer us as alternatives in this time of extended crisis for the people who are fighting hardest to keep Guatemala from complete state repression? How can we redistribute resources to folks on the frontlines without compromising anyone’s safety?

I am deeply moved by the wealth of knowledge that we hold as a multiracial and intergenerational network. To the elders who were organizing during the 70s and 80s, what advice do you have for us in this difficult time? To our BIPOC comrades who are on the frontlines of struggles for immigration and racial justice, what vision do you have for NISGUA’s role in internationalist solidarity? To all of us, what is your vision of a liberated world, and how do we build it?

Leave A Comment