Internacionalista Taz (they/elle) wrote this reflection in August 2025.

Late July, it is hot in Santa Anita las Canoas, the small Maya Kaqchikel community in Chimaltenango, a department in the central highlands of Guatemala. The dirt glows orange. Leaves of the coffee trees shift and shimmer.

Don Aguilar(1) sits quietly on a small stool to my left, both feet on the floor. He is one of only two men in a large group of massacre survivors we came to visit and accompany. When he addresses us for the first time, he begins firmly, leaning towards us, holding a steady gaze. As he continues his testimony, his voice cracks, tears dripping into the coffee cup between his knees.

He was just a boy on the 14th of October 1982 when the death squad appeared in his village. They rounded up men and women, accusing them of being guerrilleros, resistance fighters.

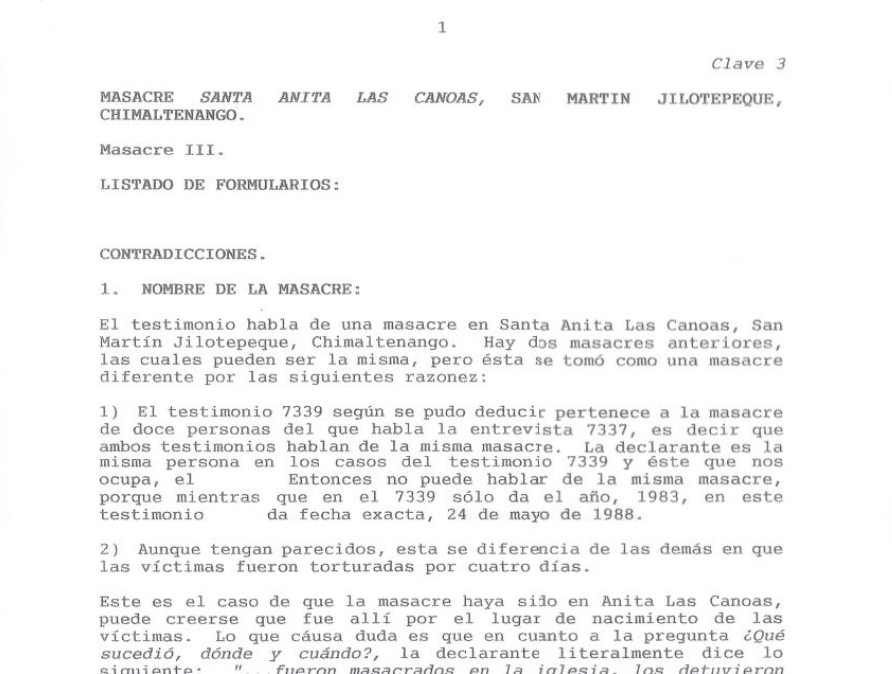

A report, part of the Proyecto Interdiocesano de Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica, recounts the events perpetrated during the massacre in Santa Anita Las Canoas in the municipality of San Martín Jilotepeque, department of Chimaltenango, and tells how a military commissioner was in charge of selecting the victims, torturing them and, together with the G-2, killing them. Archive of the Human Rights Office of the Archdiocese of Guatemala, 1997.

A summary (see picture above) of the Santa Anita massacre is included in the 1997 report prepared by Archbishop Juan José Gerardi, who was himself assassinated upon the publication of his research. The death squad seized people at random, bringing them to the church at the center of town. Torture and mass rape are recorded. At 10 AM the next morning, the survivors were shot. The army left their bodies piled in front of the church.

“Mi papá,” Don Aguilar cried, “mis hermanas.” My father, my sisters.

This was the first time he had given his testimony. He had waited his whole life to fight for justice for his family, he told us, because he had spent the last 18 years performing backbreaking labor in the United States. He pruned trees in Georgia, picked strawberries in California, built sidewalks and roofs in New Jersey. All the while, he sent money home to his mother, praying for the day he had the funds to return.

In the six months I have been in Guatemala working with Xinka and Maya land defenders, I have yet to meet someone without family in the United States. Every day, 1,000 Guatemalans leave the country for the U.S., and 9 in 10 leave because of a lack of economic opportunity. Though there are no formal statistics on indigeneity and migration, the relationship is inferential: 74% of Indigenous people in Guatemala are impoverished, compared with 56% of the general population. Gruesome stories of Maya children, women, and men brutalized and detained at the US border have filled headlines for decades.

In her 2021 book Border & Rule, Harsha Walia demonstrates how “mass migration is the outcome of the crises of capitalism, conquest, and climate change.” She frames migration as dual crises of displacement and immobility: preventing the freedom to stay and the freedom to move.

View of the land around Chiapastor community, where many massacre survivors live. Near by are the Mixco Viejo ruins, the capital of Chajoma, a 12th century Kaqchikel city. Photo by NISGUA, July 2025.

Don Aguilar did not want to leave his land, his family. After hearing his story, I wanted to better understand the global economic systems that have generated this fresh wave of dispossession and violence against Indigenous peoples in Guatemala. By studying how the historical conditions from which the trade agreement dominating the Guatemalan economy, US-CAFTA-DR, emerged, I have a clearer idea of how US policies of neoliberalism have created a crisis of displacement that push the Indigenous people of Guatemala off their land, into poverty, across the border to survive, an act that splits families, kills communities, and severs life-giving relationships with land.

Broad historical context: Neoliberalism as counterrevolution

Walia defines neoliberalism as an “ideology of individualism and competition, paired with enhanced enforcement to coerce labor while policing impoverishment.” It is both a cultural system— an idea that shapes people’s identities and relationships— and an economic system that has restructured the world since the 1960s and accelerated in the ¢80s and early 2000s. Central tenets include the defunding of welfare and social support systems, deregulation of environmental protections and labor conditions, tax breaks and legal restructuring to protect corporate profit, and the privatization of public services, which turns basic necessities like water and electricity over to generate profit for megacorporations. Neoliberalism accompanies globalization, the cracking open of local economies.

Considering the historical context from which it emerges, I understand neoliberalism as a counterrevolution to the massive changes social movements won in the first half of the twentieth century. Organized labor, including enormously popular organized Communist and Socialist mass movements in the United States, won social reforms, implementing the social safety net, creating standards for labor conditions, and transforming culture. Later, the Black liberation and radical feminist movements had the potential to undermine the social structure of capitalism by removing the base of unpaid and exploited labor upon which US capitalism depends. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, the US government descended into crisis. Deep recession fed social movements, and despite slaughtering 3.8 million people in Vietnam, the world’s largest and most expensive military lost a resounding defeat to Indigenous communist guerrilla fighters.

As Walia puts it, “The ruling class set out to restore US capitalism via neoliberalism.” Under the influence of the infamous Chicago School, neoliberal policies sought to reimpose Western imperial supremacy through wars on Central and South America while normalizing carceral governance at home through the war on drugs, border militarization, and building the prison-industrial complex.

Mapping US policies of neoliberalism in Guatemala

Pre-’80s: Corporate–Backed Coups

Neoliberalism in Guatemala can be understood as an evolution from the imperial extraction and control that began in 1524 with Spanish colonization. Here I want to name a dynamic that helped set the groundwork for the full expansion of neoliberalism in the ’80s.

In Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954-1961, Stephen Streeter tracks the steady rise in US corporate control, trade domination, and access to Guatemalan resources through the beginning of the revolution. While it was the Texas Dulles brothers of United Fruit Company (UFCO, now Chiquita Bananas) behind the original coup in 1954, this shifted as neoliberalism arose. Industries dubbed the “Sunbelt corporations” from Florida, Texas, and Southern California, representing real estate, defense industries, and petroleum, sought expansion into Guatemala. They needed a pro-Western government to do so, one that the Indigenous sovereignty and communist movements were directly opposed to. These forces helped prop up early military dictatorships. The Castillo Armas administration alone received $45 million in US grant aid at the lobbying request of the Sunbelt Corporations, over half a billion in today’s terms.

The legacy of extraction: A political cartoon illustrating how the United Fruit Company epitomized America's economic imperialism in Guatemala and Central America—a pattern of resource exploitation that continues to shape regional dynamics today. Cartoon by Bain.

’80s: Genocidal “Anti-Communism”

While Reagan’s “war on drugs” at home provided excuse for criminalizing the poverty that resulted from his neoliberal economic agenda, the rhetoric of anti-communism in Central America provided cover for suppressing resistance to US imperialism and exploitation.

The United States funneled around $120 million dollars in direct military aid (nearly half a billion in today’s terms) to Guatemala in the 1980s to back a series of genocidal military dictators, most infamously Benedicto Lucas Garcia, Fernando Lucas Garcia, and Efraín Ríos Montt, who carried out massacres, torture, rape, in Maya communities including Santa Anita in 1982-83, the bloodiest period of the 36-year conflict. Massacres of Maya peoples often cleared the way for US-owned extractive industry projects, like the 1980-82 Río Negro Massacres, in which over 5,000 Maya Achi people were killed to construct the Chixoy hydroelectric dam, financed by the World Bank.

From 1946 on, the School of the Americas in Georgia welcomed hundreds of thousands of mercenaries to Fort Bennington, training them in torture techniques, mass execution strategies, and coup plans. By even 1976, the school boasted to Congress that its graduates had overthrown 13 constitutional governments in Central and South America. George Kennan, cited as the architect of post-World War II U.S. foreign policy and the brain behind “special operations” military force, openly named the goal of foreign policy to be “stability for continued economic relations”, re: continued U.S. plunder. That desired stability could be achieved by propping up a dictatorship, or, if possible, simply by imposing a trade deal.

’9os and on: “War on Drugs” abroad & US-CAFTA-DR

The terms of the 1996 peace accord that ended the internal armed conflict opened Guatemala to new neoliberal models of exploitation. Having succeeded in using the “war on drugs” language to mask neoliberal violence within the United States, policymakers turned outwards, using the same language of “war on drugs” to justify continued military intervention in Central America to prop up big industry. As Dawn Paley writes, “The war on drugs was a long-term fix to capitalism’s woes… cracking open social worlds and territories once unavailable to globalized capitalism.”

The formal cracking open of Guatemala’s resources post-conflict came as a trade agreement. US-CAFTA-DR is the binding deal governing economic relationships with the United States. It has reshaped Guatemala in its neoliberal image since 2006. CAFTA was modeled heavily on NAFTA, the 1994 agreement that decimated Mexico’s local economies. Like NAFTA, CAFTA saw industries deregulated, public resources commodified, and corporate property rights extended. I will focus on two policies I have personally seen impact the Indigenous communities I work with here: tariff elimination on US goods and land grabs.

Mateo is a Xinka farmer who grows corn and black beans using ancestral methods that honor the seeds and land. He remembers being a teenager going to the market with his father to sell their goods— and finding new venders selling white bags stamped USA for half the price of their local product. CAFTA eliminated all tariffs on US agricultural goods. This flooded local markets with artificially cheapened and genetically modified US agriproducts, destroying local traditional agrarian economies. Corn, maiz, is holy, at the center of both Xinka and Maya cosmology. Flooding the market with American corn, subsidized by the US federal government at a rollicking rate of one million dollars per minute, is an attack on Indigenous food sovereignty. In Guatemala today, commercial agribusinesses control 65%, over two thirds, of airable land. There is no direct data on how small Indigenous farmers like Mateo have been affected by CAFTA, however reports suggest it could be comparable to the impact NAFTA had in Mexico. Within the first decade of its implementation, 1.3 million Mexican farmers were driven into bankruptcy and forced off their land.

Soon after Mateo took over his father’s small farm, he faced another life-altering threat tracing directly back to neoliberal expansion: the opening of El Escobal, an American and Canadian-backed silver mine, touted as the largest in Central America, in his people’s land. Within months of operation, the rivers and groundwater in the community disappeared completely. The mine’s exhaust pipe released chemical-laced air so hot, potential rain clouds in the region were dispersed. Mateo could not grow his milpa. When he and his community organized a peaceful resistance to monitor the mine, they were attacked by the mine’s security.

CAFTA changed regulatory laws and opened the doors to land grabs for megaprojects like mines that decimate the land, kill land defenders, and export profit back home to the United States. As Maya K’iche leader Aura Lolita Chávez Ixaquic put it, “The macroeconomic and neoliberal model creates laws to open the doors to multinational companies to invade our territories without consulting with or providing information to us.” The Observatorio de Industrias Extractivas, a independent watchdog group monitoring extractive industry in Guatemala, is currently tracking 57 major extractive projects, each with devastating ecological and violent implications for the often Indigenous communities living on the land, and each owned, operated, or financed by foreign investors.

Conclusions: Neoliberalism and resistance in the case of Don Aguilar

When we spoke with Don Aguilar, we sat on the clean concrete porch of someone’s niece. The house was new, built with remesa, money sent back home from a loved one working al norte, in the US. Remesa, another survivor made sure to stress to us, is the only thing that has allowed some of her community to stay in Santa Anita, to live and work there with dignity.

Migration is a right. The United States, a settler colony, has no right to enforce borders on First Nations land it illegally occupies. As Maya Kaqchikel organizer Silvia Raquec Cum put it, “From the perspective of Indigenous peoples, migration has always existed as a form of exchange and communication within the dynamics and life of our communities. We have seen how the United States began to build its borders and divide towns, creating physical and ideological barriers, and how, in spite of this, people still continue to migrate.”

Don Aguilar did not make the decision to migrate freely. After surviving the US-sponsored genocide in his community, the murder of his father, he faced an economic crisis so dire he was forced to leave his remaining family to survive. Neoliberalism creates the conditions of forced migration and forced disorganization of community that further dispossesses Indigenous people from one another and their ancestral lands. In the testimony of Don Aguilar, I see the heavy footprints of US violence and intervention.

I also see the force of resistance. Though a lifetime of labor and borders away, he maintained connection with his community. He returned, older now, but ready to organize, to demand justice for his family and village. Over coffee, tamales, and soup, we chatted about Kaqchikel, his soft and clipped native language, which he spoke with the other organizers. He had missed speaking it in all his years away. I asked him what he dreams of for Santa Anita las Canoas. “Justicia”, he said, his eyes closed, smile so wide the gold bar between his teeth glinted. “Liberación.”

Sources and suggested further reading:

- Harsha Walia: Border & Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism

- Dawn Paley: Drug War Capitalism

- Stephen Streeter: Managing the Counterrevolution: The United States and Guatemala, 1954-1961

- Jack Nelson-Pallmeyer: School of Assassins

- Guatemala: Nunca Más

- Carlos Eduardo Martins: Dependency, Neoliberalism and Globalization in Latin America

- Barker, Dale, Davidson: Revolutionary Rehearsals in the Neoliberal Age

(1) All names of land defenders in this article have been changed to pseudonyms for safety.

Leave A Comment