Guatemala plunged into a political crisis this month as President Jimmy Morales attempted to circumvent a criminal investigation into his campaign finances by declaring the head of the UN-sponsored Commision (CICIG) persona non grata, a decision that sparked widespread public outcry. A second wave of outrage followed over legislation passed by Congressional representatives. The legislation, popularly called the #PactodeCorruptos (Pact of the Corrupt), sought to protect politicians from anti-graft measures. Revelations that President Morales has been on the receiving end of a “military bonus” added fuel to the growing crisis. Protesters who filled Parque Central on September 14 were met by military police and, despite the President’s cancellation of Independence Day parades, student-led civilian protests continued on September 15. A national strike is taking place on September 20, calling for the resignation of President Jimmy Morales and all of the Congressional representatives who voted for the #PactodeCorruptos. Read our summary on the lead-up to the national strike in our recent blog, “Political crisis as corrupt officials seek to undermine advancements in the fight against impunity”.

Here we share perspectives from current accompaniers as they continue their accompaniment work amidst the political storm. Chris Shorne provides an excellent summary of the initial phase of the political crisis and Clara Lincoln highlights the work that continues despite national turbulence and makes parallels between private security abuses in the U.S. and Guatemala. Read their letters below.

From Chris Shorne: “Ni Corrupto, Ni Ladrón: The Presidential Crisis and its Connections to the Past”

Dear Friends and Family,

In case you haven’t heard, Guatemala has fallen into a political and diplomatic crisis this week. It turns out that the comedian-turned-president who ran on a platform of being neither corrupt nor a crook (ni corrupto, ni ladron) might be both. His party, the National Convergence Front, FCN, is made up of ex high-ranking military officials suspected of war crimes. I’ve tried to put the situation into clear terms below and I’ve included context to help clarify how it relates to international accompaniment.

On Sunday morning at 6am, Guatemalan president Jimmy Morales tried to expel the head of an international commission that investigates corruption. Why? In their investigating, the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala, known as CICIG, found evidence that president Morales’s party received illegal campaign funds. In Guatemala, presidents have political immunity, meaning they cannot be charged with crimes. The commission and the Guatemalan attorney general asked the courts to strip the president’s political immunity in order to charge him. Less than 48 hours later, President Morales ordered that the head of the CICIG, Iván Velásquez, be expelled from the country. The Constitutional Court blocked the expulsion order.

RECAP:

Commission Against Impunity: We’re going to charge you with a crime.

President Morales: I’m going to expel you from the country.

Constitutional Court: Um, no.

CONTEXT

Why is there an international commission here in the first place?

The International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala was formed to help Guatemalans move their government from one that attempts to destroy entire peoples (genocide) to one in which its people rule (democracy). The commission, known by it’s Spanish acronym CICIG, was formed in 2006 in a partnership between the Guatemalan Government and the United Nations. CICIG’s mandate is to investigate current crimes, not past crimes. But as this crisis and other recent history shows, the crimes of today are not separate from the crimes of the past.

When the peace accords were signed in 1996, those in power stayed in power, even though their positions may have changed. Excellent journalism about this continuity of power can be found here, here, and here. As a recent Guardian article notes: “CICIG was created to help dismantle parallel security structures and organised crime rings dating back to the [Internal Armed Conflict].” Dismantling these corrupt structures and creating a democracy is, necessarily, a long hard process. It is the work that, in one way or another, is being done by everyone we accompany.

Whether it is the Xinca who went to the Supreme Court yesterday to say we are here and we do not want your Escobal Mine (with offices in Reno, Nevada) or the witnesses in the Ixil genocide trial against Ríos Montt who are still waiting for the retrial to start; whether it is the Q’eqchi’ living along the Cahabón River who two days ago voted 26,537 to 11 against the Oxec dams, or those in the capital today protesting corruption. All of these people, in their ways, are working to transform a government that would try to kill its people into a government run by its people.

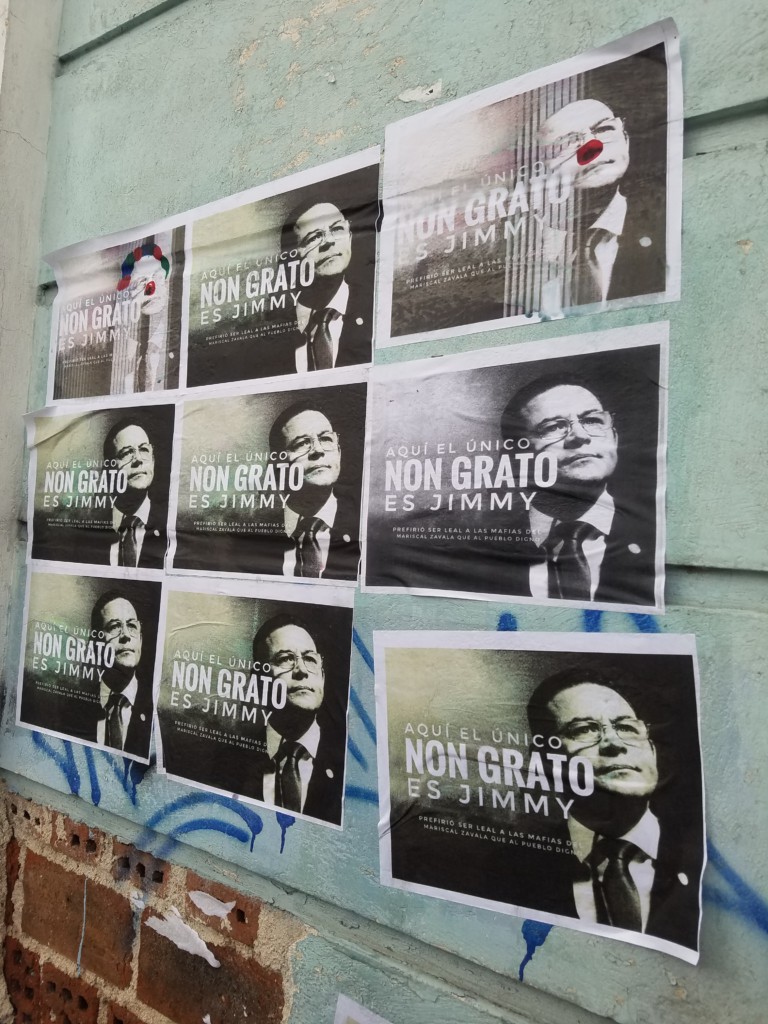

Street art in Guatemala City that says “Aquí el único non grata es Jimmy” (Here the only non grata is Jimmy). Some of the pictures are drawn on to make Jimmy look like a clown, which was his profession before becoming president. Photo and caption: Clara Lincoln

From Clara Lincoln, “Private Police: DC and Guatemala”

Sunday morning I woke up at 6am and piled into a double-cab pickup truck with four other people: one coworker, one person from Protection International (PI), and two journalists from the Observer. PI provides workshops on security and safety to movements in resistance around country. The Observer does investigative journalism around mega-projects to find all the sneaky details that resistance movements can use—for example which projects actually have what licenses and how they got them. We decided to have breakfast in another city about an hour away. My coworker, looking at her phone, suddenly said, “Jimmy is trying to expel Iván Velasquez from the country.”Iván Velásquez, head of the United Nations anti-corruption commission known as CICIG for its initials in Spanish had called last week for an official investigation and trial against Guatemalan President Jimmy Morales. The CICIG has evidence that Jimmy Morales accepted and then covered-up illegal campaign donations. Now Jimmy, as he’s commonly called, is trying to expel the head of the CICIG from the country by naming him persona non-grata. Why is he so scared of Iván? The CICIG began as an agreement between the Guatemalan government, influenced by human rights organizations, and the United Nations. It aims to “strengthen the rule of law in a post-conflict country.” Two years ago, when it was time to renew the CICIG for another two-year period, then president Otto Pérez Molina initially said he would not renew the mandate. At the time, two growing corruption scandals were getting dangerously close to his own chair. Amidst months of protests with thousands of people, he renewed the CICIG’s contract and, a few months later, he had resigned and was behind bars for corruption.

The fact that Jimmy would attempt to expel Iván, even though that goes against Guatemala’s contract with the United Nations, suggests that the CICIG is probably about to reveal a scandal of similar proportions involving Jimmy. Jimmy was supposed to be different—the former comedian with no experience in politics ran on a platform of “Ni Corrupto, Ni Ladrón” (neither corrupt nor a crook). However, his party is made up mostly of high-ranking ex-military officers. He is no different from those who have been in power since the internal armed conflict.

The longer I’m here, the more parallels I see between the systems of power and repression in the US and in Guatemala.On September 27, 2009, Adolfo Ich, German Chub, and other community members were gathered in the town of El Estor that sits on the largest lake in Guatemala, Lago Izabal. They were continuing their protest of a destructive nickel mine that was polluting their land and water. That day, the company’s security and legal forces arrived to evict the community. According to witnesses, a private security guard for the mine fired into the crowd, killing Adolfo and wounding others, including Gérman Chub, who is now paraplegic. Since then, Adolfo’s wife Angélica Choc and Gérman have made up part of the team that has fought for justice for their community, and we have accompanied them in their struggle.

Angélica Choc giving a speech on Earth Day (Día de Madre Tierra) in El Estor. Photo: ACOGUATE

Last year, the court case against the security guard, Mynor Padilla, began its public debate phase. This April, the judge gave her verdict: Padilla was absolved of all crimes. As if that wasn’t enough, the judge recommended that Angélica and all of the other witnesses, except Gérman, be investigated for providing false testimony.

This case reminds me of the case of Alonzo Smith, killed by two special police officers in DC in 2015. The Black resident of Southeast DC was found face down and unconscious in a stairwell of a private apartment complex after an altercation with two special police officers who, when the police arrived, put handcuffs on him before starting CPR. He died a few hours later in a hospital. An autopsy ruled the death a homicide.The police waited more than 24 hours to call Alonzo’s mother, Beverly Smith. They have given her little information and she still doesn’t know why he was at the apartment complex. Special police forces, according to an article on ThinkProgress, “are not quite full police officers, but they’re more than security guards. They are a private police force, empowered to make arrests and carry guns. But because they work for private contractors and not public agencies, their actions are often shrouded in mystery.”

Last summer I interned for an organization in DC called ONE DC. I was involved in the struggle to protect affordable housing at a private-public complex called Brookland Manor. There, private police have attempted to suppress ONE DC and Brookland Manor residents from organizing and canvassing. A video of one encounter can be seen here.

The article on ThinkProgress notes that security companies like those at Brookland Manor and the apartment complex where Alonzo Smith was killed operate with less scrutiny than traditional police departments: “These companies establish their own standards and procedures, disciplinary measures, and managerial discretion. They are then hired by local businesses, government agencies, schools, and developers who might want extra security in their buildings— many of which are occupied by poor residents of color.”In Guatemala, private police are often, like Mynor Padilla, ex-military. They serve similar functions today as they did in the time of the Internal Armed Conflict: protecting the interests of the transnational rich and powerful. The Internal Armed Conflict was the result of a CIA-orchestrated coup that served to protect the United Fruit Company’s interests in Guatemala. During the worst of the internal armed conflict, Mynor Padilla was serving in the military in the West of the country. And in 2009, Padilla did his job of protecting the interests of the Canadian country HudBay minerals, owner of the nickel mine that Adolfo opposed. He killed a peaceful protester and went free.

Angélica is still struggling for justice, moving forward with an appeal of the sentence, just like Alonzo Smith’s mother who won’t stop searching for the truth. Both women of color face an uphill battle, confronting a new beast in privatized security guards who seem to work in a system of even more impunity than regular police forces. In Guatemala, the CICIG may eventually achieve its goal of pushing the justice system towards real justice, but there is a lot of work to be done—in both countries.

Leave A Comment